Prize Winning Problem Question

The 2009 Busfield Prize - winner Zizhen Yang

The Incorporated Council of Law Reporting Busfield Prize is awarded for the best performance in the skill of Legal Research (on the BVC). The annual prize is a fitting memorial to Miss K. Busfield who bequeathed the funds in order to help reward the achievements of students. During her working career Miss Busfield was known for mentoring students, and providing support to those just beginning in the law profession.

In 2009 the prize was awarded to Zizhen Yang. Her research is outlined below... (introduction by Louise Carlin)

The Problem

Ms. D is a professional actress. She appeared at a well known theatre as the female lead in a play featuring graphic scenes of a simulated rape, as well as verbal and simulated physical violence towards her character. In a post-performance discussion at the theatre, Mr. R — a well known theatre critic — made a number of criticisms about the play, labelling it distasteful, and in particular criticised Ms. D for:

- (i) the quality of her performance, calling it “particularly hysterical” (“Statement-1”);

- (ii) her contribution to the promotion of violence against women (“Statement-2”); and

- (iii) her failure to look beyond the prospect of fame and fortune that the play brought her (“Statement-3”; together “the Statements”).

Ms. D was asked about her motivation for doing the play in several auditions she attended in the weeks following the discussion, and was not offered any of the parts. She thus wrote to Mr. R, objecting to his comments and asking him to print a retraction in the local newspaper. Mr. R’s reply was short: he had given his comments on the play and its performance as he had been invited to do and, in his view, what he said was both reasonable and fair.

Ms. D has not obtained any new acting work to date. She now comes to you and wants to know:

- (i) whether a court is likely to find Mr. R’s comments defamatory and Mr. R liable for defamation;

- (ii) whether Mr. R is likely to succeed in the defence raised in his reply; and

- (iii) should proceedings be issued, whether she could have the matter determined, including an order publicising any judgment in her favour and compensation for her continued unemployment in the theatre, without a full trial.

The “Answer”

There may not be a “right” answer to a legal research problem. A problem that invites genuine debate almost certainly has no “correct” answer. Given below are my personal conclusions to Ms. D’s problems.

I. THE LIKELIHOOD THAT THE COURT WOULD FIND MR. R’S STATEMENTS DEFAMATORY AND MR. R POTENTIALLY LIABLE FOR DEFAMATION

A. Are Mr. R’s Statements Defamatory?

The Statements are clear in their natural and ordinary meaning. They are defamatory in law if they tend to lower the claimant in the estimation of right-thinking members of society generally 1. To say that Ms. D is incompetent at her profession will be defamatory because the words impute a lack of skill, capability or efficiency in the conduct of her professional activity and the resultant injury to her professional reputation is enough 2. It has been held defamatory to write of an actor that he cannot act3. Breaches of professional ethics or codes of conduct are actionable whereas mere breaches of etiquette are not4. To allege that Ms. D has selected her roles motivated by fortune and fame and to the abandonment of any moral direction is an allegation of a failure to conform with modern ethical standards.

B. Are the Defamatory Statements Actionable Against Mr. R?

As the Statements are spoken, Ms. D’s claim lies in slander. Slander is generally only actionable upon proving special (i.e. actual) damage. One exception is where the words are “calculated to disparage the plaintiff in any office, profession, calling, trade or business carried on by him at the time of the publication” (s.2, Defamation Act 1952).

A statement that the acting of a professional actress is “hysterical” objectively discredits her as an actress, and is therefore actionable per se. Statements-2 and -3, which are not peculiar to Ms. D’s profession and would be defamatory if published of others, are actionable per se if they are likely to adversely affect her professional reputation in the eyes of reasonable people. As reasonable people do not generally hold moral integrity to be any more essential in actors than in non-actors, it is unlikely that these would satisfy the s.2 test. They are only actionable upon proof of special damage (the loss of some “material” or “temporal advantage” which is “pecuniary” or “capable of being estimated in money”)5, which has been caused in fact by, and which is the natural and probable result of, the defamatory publication.

A refusal of employment, for which Ms. D would have been remunerated, on account of the slander would constitute special damage6, but the decrease in the number of auditions is unlikely to constitute “pecuniary” loss. Ms. D needs to demonstrate that, as a result of the Statements, it might “fairly and reasonably have been anticipated and feared7” that her failure to secure further parts would follow. That she was asked about her motivation for doing the play in several auditions may be strong indication of this causal relationship.

II. THE LIKELIHOOD THAT MR. R WILL SUCCEED IN THE DEFENCE RAISED IN HIS REPLY

Mr. R raised the defence of fair comment in his reply. The successful defence requires that the words complained of are comment and not a statement of fact; that there is a factual basis for the comment, which is contained or referred to in the matter complained of; that the comment is “fair”; and that the comment is on a matter of public interest. The burden of proof in establishing these elements is on Mr. R, and the tests are objective.

A. Comment not Fact:

A comment is “something which is or can reasonably be inferred to be a deduction, inference, conclusion, criticism, remark, observation, etc”8. Critical reviews of plays and performances are generally regarded as comment9,10.

Mr. R’s statement as to the calibre of Ms. D’s acting is one purely of evaluative opinion, which cannot be objectively verified, and is therefore a comment. Of value is the decision in Buffery11, the facts of which are very similar to those at hand. The defendant reviewer in Buffery had written, in view of the violence and horror featured in a television programme, that the claimant actress, in choosing to participate, “[had] no conscience” and “should be thoroughly ashamed”, and of the acting that “[t]here was nothing going on beneath the surface here; the cast walked through it like zombies”. Gray J held that “it would have been apparent…that the reviewer was basing himself on what he inferred about the quality of the programme…and the appropriateness of the decision of the actors to be involved in a television programme of that kind. To the extent therefore that reference is made in the review to [the claimant’s] state of mind and her lack of conscience…there is, in my view, a realistic prospect of the [defendant] establishing that this is and would have been recognised by readers to be a comment”. This reasoning would apply equally well to an oral review of a stage performance as to a written review of a television programme.

B. The Factual Basis for the Comment:

The factual bases for Mr. R’s statements lie in the subject matter of the play and the reputation of the theatre, to both of which he referred expressly. For fair comment to apply these supporting facts must be true in themselves, which they quite evidently are. That there would be some who received Mr. R’s statements through repetition, who did not see the play and therefore had no opportunity to judge whether the comments were ones that were based on fact, cannot defeat Mr. R’s defence at law12.

C. “Fairness” of the Comment:

The Statements will be “fair” provided that they are comments that could have been made by any honest man, however prejudiced and however exaggerated or obstinate his views13.

Statement-1, that Ms. D’s acting was “particularly hysterical”, is almost certainly fair for any honest person could form such a highly negative opinion. As to Statement-2, in view of the subject matter of the play, a person could quite honestly conclude that any participating actor was not overly concerned with possibly contributing to the promotion of the type of violence featured. When Statement-3 is read (as it must be) in the overall context of Mr. R’s review and combined with the graphical violence of the play, it is arguable that a person could honestly conclude that Ms. D had superseded any consideration of contributing to the promotion of violence with considerations of fortune and fame.

D. Matter of Public Interest:

It is for the judge alone to decide whether the matter commented on is one of public interest.

Performances and productions at public theatres are matters of public interest, and this includes the performance of individual artistes14. It was held in Buffery15 that “the calibre of the performance of the actors and the decision of the actors to participate in the programme” are both matters of public interest. This applies directly to bring Mr. R’s statements within the ambit of his defence.

III. COULD MS. D HAVE THE MATTER DETERMINED, WITH DAMAGES AND AN ORDER PUBLICISING ANY JUDGMENT IN HER FAVOUR, WITHOUT A FULL TRIAL?

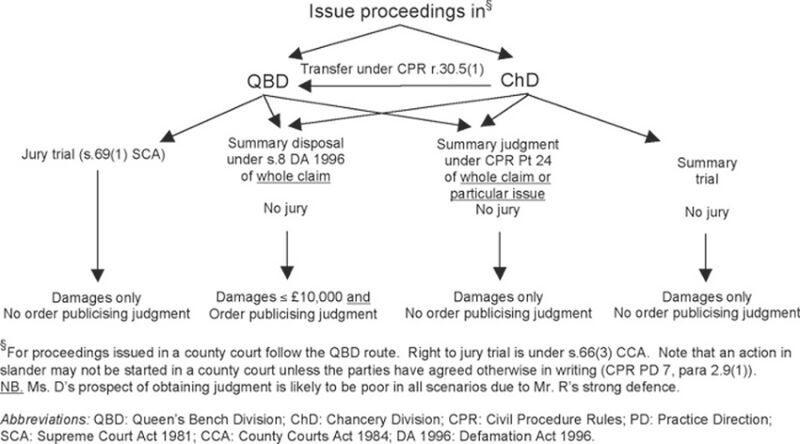

The choices available to Ms. D in relation to where she can issue proceedings and the corresponding remedies available are summarized in the diagram below.

References

Many thanks to Louise Carlin and the ICLR for allowing us to reproduce this article (originally published in the ICLR Student Winter Newsletter 2009. Zizhen Yang completed both her GDL and BVC at the City Law School and was called to the Bar in 2009.

- Sim v Stretch [1936] 2 All ER 1237↩

- Drummond-Jackson v BMA [1970] 1 WLR 688↩

- Duplany v Davis (1886) 3 TLR 184↩

- Angel v Bushell [1968] 1 QB 813↩

- Chamberlain v Boyd (1883) 11 QBD 407↩

- Sterry v Foreman (1827) 172 ER 270↩

- Lynch v Knight (1861) [1861-73] All ER Rep Ext 2344↩

- Branson v Bower [2001] EWCA Civ 791↩

- Burstein v Associated Newspapers Ltd [2007] EWCA Civ 600↩

- Buffery v Guardian Newspapers Ltd [2004] EWHC 1514↩

- Buffery v Guardian Newspapers Ltd [2004] EWHC 1514↩

- Buffery v Guardian Newspapers Ltd [2004] EWHC 1514↩

- Merivale v Carson (1887) 20 QBD 275; modified in Turner v MGM [1950] 1 All ER 449 and Convery v Irish News Ltd [2008] NICA 14↩

- McQuire v Western Morning News [1903] 2 KB 100↩

- Buffery v Guardian Newspapers Ltd [2004] EWHC 1514↩